Long before the Tuskegee Airmen became the heralded group of heroic World War II aviators we’ve come to know, they were simply referred to as the squadron of Negro pilots who trained at Tuskegee Institute. In fact, after the war these men were turned away from military, commercial, and freight pilot jobs because they were Black.

It took years before they received the recognition they deserved. Then just recently, this current administration dared to erase them from American history by scrubbing their story from all Defense Department’s training materials, websites, and even Arlington National Cemetery.

Needless to say, the outcry was swift and strong. Powerful enough to force the reinstatement of the Airmen’s record of distinction, along with a flimsy apology by Defense officials: My Bad. It was an accident.

Sure it was.

The past few months have made it even more clear to me that we must not only be diligent about preserving our important narratives, but we also have the opportunity to amplify lesser-known stories. People are paying close attention to history right now, and there are numerous hidden figures that have contributed to the well-established stories we hear about the most.

In the case of the Tuskegee Airmen, those gentlemen most likely wouldn’t have achieved greatness during the war had it not been for the brilliant work and support of the Tuskegee Weathermen.

Keep in mind that the pilot training program at Tuskegee was put together quickly, the result of a couple of things. First, President Roosevelt was feeling the heat. The Black community had been extremely vocal about not having representation in the military insofar as skilled positions were concerned. Mary McCloud Bethune, one of Roosevelt’s advisors and a close friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, was leaning in the president’s ear on this matter.

Second, Yancey Williams, a pilot and Howard University student, filed a lawsuit against the War Department in 1941 for their refusal to admit him into the Army Air Force’s cadet program because he was Black. He won his case, and that led to the creation of the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the Black pilot training program at Tuskegee.

As it was and will always be—aviation and meteorology are inextricably linked. One drives the other. So, flying squadrons were required to have weather officers on staff, but because the military was segregated during WWII, the Tuskegee pilots needed their own weather detachment. Problem was, there were no Black weather officers in the Army at that time, and only about 60 weather officers total.

White military officials had already decided Blacks weren’t capable or intelligent enough to fly planes in battle, and that was definitely the sentiment regarding Black servicemen who desired training in the area of meteorology.

Nevertheless, if the Tuskegee program had any chance to succeed—even as military officials held little expectation that it would—it was going to need a small contingent of weather forecasters with a background in math, engineering, or science. After an exhaustive search by the Army Air Force, officials at MIT identified a suitable candidate, Wallace P. Reed, a mathematics major and graduate of the University of New Hampshire.

Reed entered the Army’s Air Corps cadet program at MIT, where he received rigorous training in applied meteorology. On February 14, 1942, he graduated and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Corps’ Weather Service, thus becoming the first Black meteorologist in the US military.

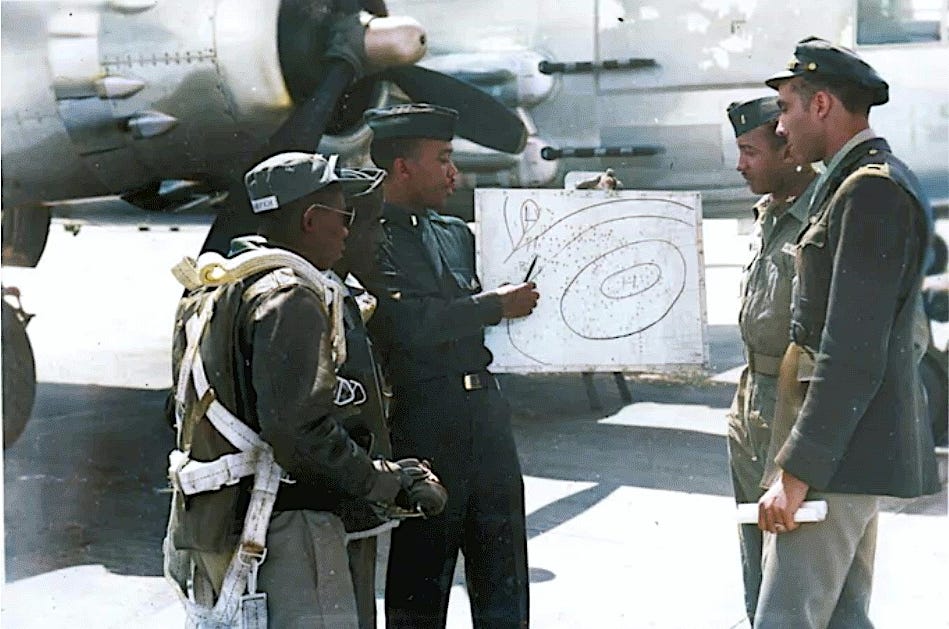

Lt. Reed was assigned to Tuskegee and tasked with getting the squadron’s weather detachment up and running from ground zero, while receiving very little support from Air Corps or US Weather Bureau personnel. That meant he was responsible for weather observations, the collection and analysis of data, and the preparation of forecasts. He also provided weather briefings to the pilots. Ultimately, Reed was joined by 14 other weathermen, and he was named commander of the Tuskegee Weather Detachment.

Against all odds and in the face of relentless skepticism, the Tuskegee pilots went on to achieve phenomenal success during WWII, with the Tuskegee Weathermen serving as the wind beneath their wings. Because of the blatant bigotry present in the military, the pilots felt safer and reassured by receiving their weather forecasts from other Black servicemen.

The fact that these weather officers exceeded expectations in a technically challenging career is alone noteworthy. That first cohort not only included trailblazers like Lt. Reed, who would become the first Black meteorologist at the US Weather Bureau (the National Weather Service), but the group would also boast a few other pioneering names:

Charles E. Anderson became the first Black American to receive a PhD in meteorology, when he earned his degree from MIT in 1960. Anderson spent much of his civilian career as a professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he was also named an associate dean.

Archie Williams, who prior to WWII, defied Hitler by winning a gold medal in track and field at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, competing alongside his teammate, the legendary Jesse Owens. Williams later earned a degree in aeronautical engineering and flew missions during the Korean War.

It is for certain, the Tuskegee Weathermen, America’s first Black meteorologists, made it possible for other Black men and women to pursue their dreams and become atmospheric scientists (including my dad). While the number remains small—something like 2 or 3 percent of all meteorologists are Black—I believe that stories like this will show our young weather geeks that the sky is not just something to behold, but it truly is the limit.

Even at a young age, Alonzo sensed those clouds were carrying more than water through the sky—they held the big dreams of a little boy, who like the rain, refused to be contained. THE WEATHER OFFICER is available NOW.

Thanks for shining a broader light on the these American heroes. These stories must be told.

I’d love to stay connected in this creative space and would be honored if you’d follow me back too. Let’s grow, write, and heal unapologetically—because this is what community looks like.

https://open.substack.com/pub/msmaine/p/recession-ready-when-the-struggle?r=1t2agi&utm_medium=ios